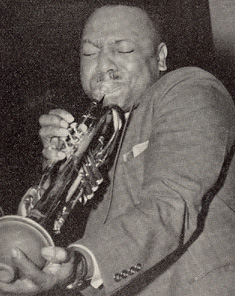

Cootie Williams was the guy who had the dubious honour of replacing Bubber Miley in the late 20's. However he was no newcomer having earned his chops by playing with such luminaries as James P Johnson, Chick Webb and Fletcher Henderson. Williams continued the "jungle" style playing that Miley and the late 1920's were renowned for. He was to become one of the most sought after trumpet players in the following two decades recording with Ellington in the 1930's and also leading his own sessions. He sensationally left Ellington's orchestra to join up with Benny Goodman and established himself in the latter's sextet.

He became a bandleader in the 1940's, no mean feat considering the logistics and costs involved especially as swing was on the wane. Yet he managed to employ musicians who would become some of the most legendary names in jazz - Eddie Vinson, Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis, Bud Powell and even Charlie Parker. It was around this time that he co-authored Round Midnight with an up-and-coming Thelonious Monk. The 1950's were not kind to Williams professionally but he did return to Ellington's orchestra in 1962 where he remained until Ellington's death.

Williams was an exceptional musician and trumpeter. He was renowned for his exquisite use of the plunger mute and phasing. Yet he could sound extraordinarily bluesy and soulful as well. Check out "Concerto For Cootie" a song that exemplifies all his attributes.

Jimmy Blanton

Any bass player who takes up a solo in a jazz band today has to thank Jimmy Blanton. While it was Walter Page who put the walk into the Basie rhythm it was Blanton (and his contemporary, Slam Stewart) who put the flair. Blanton employed the use of "pizzicato", a very common technique in today's jazz world but positively revolutionary when Blanton joined Ellington's orchestra in 1939, just shortly before Ben Webster. Many regard the Blanton-Webster period of Ellington's career as a particular golden age.

His career was to be appallingly short as he was to contract tuberculosis and pass away in 1942. His legacy was in his becoming known as "The Godfather Of Bebop" yet one can only wonder how his career would have been shaped in happier circumstances.

Have a listen to Pitter Panther Patter and see exactly what I mean.

Rex Stewart

Cornet player Rex Stewart had been around the jazz scene for quite a while before joining Ellington's orchestra in 1934. He was probably best known for his work with Elmer Snowden and in the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra in the mid 20's. He was to feature prominently in his eleven year stint with Ellington including writing the sublime Morning Glory.

Johnny Hodges

Probably one of the most famous names in jazz to come from Ellington's orchestra. When it came to alto saxophone there were few better. Ellington played up his smooth vibrato-heavy tone in the compositions that he wrote for Hodges. (No surprise in the fact that he was a massive fan of Bechet). He joined the band in the late 1920's and was its leading soloist by the mid 1930's. He could play the blues with the best of them but perhaps it was the ballads that Ellington wrote for him that would become Hodges bread and butter in his later career. (Check out Warm Valley from 1940 as case in point). He left Ellington's big band in 1951 to pursue a solo career and made some wonderful recordings with Norman Granz. He eventually returned to the orchestra in the mid 50's and remained there until his death in 1970.

Harry Carney

Harry Carney was more than just the baritone saxophonist of the Duke Ellington Orchestra (although he was one of the earliest exponents of the instrument). He was its longest serving member joining as a 17 year old in 1927 right through to Ellington's death in 1974. He was also a friend and confidante to the Duke with the two of them riding to shows in Carney's Imperial car. These moments provided the relaxed ambience for Ellington to compose some of his most memorable songs. He was a master of the clarinet but it was with the rather unwieldy baritone that he was to make his name. He was one of the first musicians to employ the technique of circular breathing which enabled him to hold long indefinite notes to embellish his solos.

Here's Sepia Panorama from the Blanton - Webster era which is a great example of Ellington's sound at this time and showcases Carney, Ellington and Blanton.

Sonny Greer

Sonny Greet first met Duke Ellington as far back as 1919 and was his first drummer when he began The Washingtonians in 1924. He was to remain in the band for almost 30 years. So when you're listening to the drums on any Ellington classic from the 20's, 30's or 40's, you're listening to Sonny Greer.

Ellington wrote of Greer in his autobiography, Music Is My Mistress, ''When he heard a ping, he responded with the most apropos pong. Any tune he was backing up had the benefit of rhythmic ornamentation that was sometimes unbelievable. And he used to look like a high priest or a king on a throne, 'way up above everybody, with all his gold accessories around him, all there was room for on the stand!''

Not only was he the drummer in those difficult early days but he was also its source of income due to his prowess on the pool table. He provided the "eating and walking around money" that they needed until they began to hit the big time.

Barney Bigard

Bigard was the New Orleans connection in Ellington's orchestra. He learned his trade at the feet of Lorenzo Tio and after moving to Chicago he played tenor saxophone with some heavy hitters in the mid 20's including Louis Armstrong, King Oliver, Johnny Dodds and Jelly Roll Morton before switching to clarinet. From the time he joined Ellington in 1927 to his leaving in 1942 he established himself as one of the finest exponents of the instrument. He also had a hand in co-writing one of Ellington's most famous pieces, Mood Indigo.

Tricky Sam Nanton

Along with Bubber Miley in the 1920's, Sam Nanton was the man that gave the Ellington Orchestra its dirty, growly edge that set it apart from the early competition. While King Oliver and Miley gave the musical world the wa-wa, Nanton gave us the ya-ya, an effect that made his instrument sound uncannily like a human voice. While such effects could prove gimmicky in the wrong hands this was never the case with Nanton who possessed the most powerful technique and proficiency.

Check him out on one of Ellington's finest songs from the late 1920´s, Black And Tan Fantasy